Time for a Wild Card!

And this one is a doozy. Unfortunately, I don't have a copy yet, but it is at the top of my To Buy list. As a fantasy enthusiast, I am really eager to read more than the excerpt below. This grand opening offering from Marcher Lord Press leads me to expect great things from them.

Today's Wild Card author is:

and his book:

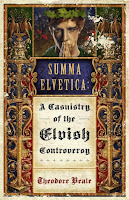

Summa Elvetica: A Casuistry of the Elvish Controversy

Marcher Lord Press (October 1, 2008)

Marcher Lord Press officially launches on October 1: http://www.marcherlordpress.com/Launch.htm

They will be giving away amazing bonus gifts to everyone who purchases Marcher Lord Press novels on opening day.

Whether you're a voracious reader, an up-and-coming novelist, or you're just buying this for your teenage son who won't read anything but fantasy, these bonus goodies will be treasures you'll love.

But remember, these bonuses are good only for those who order books on Day 1.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Theodore Beale is an American living in Europe. He has published decidedly Christian speculative fiction with decidedly secular publishers: Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.

Theodore Beale is an American living in Europe. He has published decidedly Christian speculative fiction with decidedly secular publishers: Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.He works primarily in the computer game industry, where he has launched and guided a small business into a successful career. He is an entrepreneur and a musician, and, if you do a little digging, you'll find he's interesting in other ways, too.

Visit the author's website.

Product Details:

Summa Elvetica: A Casuistry of the Elvish Controversy, Theodore Beale, Marcher Lord Press, October 2008, $12.99

AND NOW...THE FIRST CHAPTER:

Marcus Valerius looked up from the faded Numidican manuscript in irritation. The light from the study window was growing dim. Already he’d been forced to light a candle in order to make out the obscure scratchings of the historian Quintus the Elder, whose colorful accounts of his encounters with the pagan desert tribes were as dubious as they were vivid. The imperative knocking at the door threatened a lengthy interruption, one that might cost Marcus what little daylight remained.

“Come in,” he called, resigned.

The latch creaked, and a familiar, sun-bronzed face peered around the corner of the door. It belonged to his cousin Sextus, whose brown eyes were dancing with mischief.

“This better be good,” Marcus warned him. “I was just getting to the part where the tribal chief is about to sacrifice the centurion to his devil-gods.”

Sextus nodded absently. “Oh, yes, you said you were going to read up on old Quintus, didn’t you? Well, if it’ll save you some time, I’ll tell you how it ends. The legions march in, the heathen see the error of their ways, and Amorr triumphs over all. Hallelujah and amen!”

Marcus stared at him, and with some difficulty, rejected the first three responses that leaped to mind. “Thank you, Sexto. Your help is…beyond words. Now, go away, please.”

His cousin grinned back at him, and maddeningly, did not leave but rather folded his arms and leaned against the edge of the entryway.

Sexto was a half-hand shorter than Marcus, but with a slim build that made him appear taller. Like Marcus and the rest of their family, his eyes were dark brown, but he was no scholar and his skin was deeply bronzed by the sun. He wore a plain white tunica devoid of any equestrian stripes, he was barefoot, and his belt was an unadorned strip of worn leather. Besides the intrinsic arrogance that radiated from him like heat from a fire, only the finely carved silver buckle clasping the belt showed any sign that he was a Senator’s son, let alone a Valerian.

“Don’t you want to know why I’m here?”

“To plague me?” Marcus guessed. “To keep me from my learning?”

Sextus steepled his hands and did his best to appear pious. The effect would have worked better if he had stopped smirking first.

“I’m here in my priestly capacity, believe it or not. The Father Superior sent me with a message for you. You’re to go before the Sanctiff.”

“What?” Marcus was sure he hadn’t heard correctly. “I’m supposed to go where?”

“To the Sanctiff,” Sextus repeated. “Yes, you, and right away, too. Father Aurelius is already on his way here—he’s to escort you to the Palace.”

He grinned and arched his eyebrows. “Now tell me what you did to get in that kind of trouble, Marco! Did I miss out on something?”

Marcus swallowed hard. This wasn’t just impossible, it was beyond imagining. Amorr had no king. The Lord God Himself ruled over the Republic. However, as the earthly head of the Amorran Church, the Sanctiff was His voice and His viceroy from the banks of the Tiburon to the shores of the Rialthan Sea.

And Marcus had no idea why the Sanctiff wanted to see him. No idea at all.

* * *

The Holy Palace boasted twelve spires ringing one massive cupola, a symbolic representation in marble of mankind’s Savior and His twelve disciples. Marcus, with Father Aurelius by his side, were being escorted into it by the Palace’s hard-faced soldiers with their red cloaks.

To Marcus’s relief they did not march him into the Hall of Judgment. That place was dreaded by every sane and sober Amorran. He had first feared they were taking him there to stand before some inquest. But instead the guards conducted them to what appeared to be a small, private antechamber just off one of the palace’s central corridors.

The room was dark, lit only by seven guttering rushlights. It was cool, but not cold, and two of the stucco walls were obscured with wooden shelves that held fat scrolls of various lengths. Marcus couldn’t see the back wall behind the lights, but he stopped looking about the room when his eyes alighted upon an elderly man sitting alone in its center.

His Holiness was reclining on an unimposing, leather-wrapped chair that looked as comfortable as it was worn with age. He wore none of the trappings of his awesome office, only the simple blue robe of a Jamite brother. The robe was darker than his cerulean eyes, which were encased by thin folds of sagging flesh and surmounted by a pair of bushy white eyebrows. But he smiled warmly at his visitors, and Marcus could easily have thought of him as someone’s good-humored paterfamilias were it not for the gem-encrusted ring of office adorning his left hand.

“Thank you for coming, Father Aurelius.” The Sanctiff’s voice was deep, but to hear it up close in this small room instead of echoing off the marble of the palace steps made it seem more friendly than intimidating. “I have received excellent reports of your work with the junior scholastics. And welcome, Marcus Valerius. I wished to see with my own eyes the latest prodigy of the Valerian House. Perhaps you shall do for the Church what your illustrious forebears have done for Amorr’s legions, hmmm?”

Marcus blushed before the Sanctiff’s praise. It was as if the old man had seen into his mind and read his deepest, most hidden desires.

“Thank you, your Holiness. I only seek to serve God and Amorr, to the best of my small abilities.”

The Sanctiff’s aged lips wrinkled in a wry smile, and he glanced toward the shadowy corner of the room.

“Admirably courteous, is he not? I should think any concerns regarding his comportment are groundless. Don’t you agree, Caecilus Cassius?”

Marcus drew in a sharp breath as a thin-faced man in a black robe emerged from the darkness, accompanied by a cheerful-looking Jamite priest in the blue robe of his order.

Marcus knew the man whom His Holiness addressed so familiarly. Or rather, he knew of him. Caecilus Cassius Claudo was the Bishop of Avienne, one of the Church’s leading intellectuals. His famous treatise, the Summa Spiritus, written on all the diverse races of Selenoth and their distinct places in the Will of God, had sparked a raging flame of lively debate that still roared through every scholastic circle in the Republic. Marcus himself had written a short commentary on the Summa less than a year ago.

“That remains to be seen, your Holiness.” Claudo’s arid voice was acerbic and high-pitched. “Certainly, a number of his expressed opinions are impudent in the extreme.”

“Oh, come now, Claudo,” the Jamite broke in, laughing. His round face was ruddy, and Marcus liked him immediately. “A refusal to abase himself before your lofty eminence does not indicate an inclination towards boorish behavior. Why, it’s nothing more than a sign of sheer good sense!”

He smiled broadly, making it clear that he was only teasing his proud colleague, then graciously inclined his head towards Marcus and Father Aurelius.

“Since His Holiness does not see fit to introduce us, I shall take the matter in hand myself. I am Quintus Servilius Aestus, a humble priest in service to the Lord Immanuel, and, of course, His Holiness. My distinguished colleague is none other than His Excellency, the Bishop of Avienus, whose work I believe you know quite well.”

Father Aestus shook their hands warmly, first Father Aurelius’s, then Marcus’s own. Marcus was in awe, for he was truly in the presence of greatness—not once, not twice, but three times over. Father Aestus was one of the few intellectuals who dared to publicly cross wits with the famed Bishop, and he was rumored to be working on his own magnum opus in opposition to Cassius Claudo’s brilliant masterpiece.

The Sanctiff cleared his throat, and Father Aestus smoothly effaced himself, but not before directing a disconcerting wink at Marcus.

“Father Aurelius, you know why I have summoned you,” the Sanctiff stated, “and your presence here answers the question I posed to you earlier. However, Bishop Claudo and Father Aestus have their own questions for your young scholar, and with your permission, I would allow them to inquire of him.”

“Of course, your Holiness,” Father Aurelius replied obediently. He was an astute man, and did not need to be told when his presence was not required. “May I have your permission to withdraw, your Holiness?”

“Go with God, Father,” the Sanctiff said, extending his left hand. “And the grace of Our Living Lord be upon you.”

Father Aurelius bent over and kissed the sacerdotal ring of office, then gave Marcus a reassuring pat on the shoulder as he left the room. Marcus suddenly felt alone and intimidated, surrounded as he was by three of the republic’s most formidable minds.

Bishop Claudo’s dry voice broke in on his thoughts. “Marcus Valerius, I have read your commentary on the Summa Spiritus. It is…not without merit. But when you say that one does not know, indeed, that one is not even capable of knowing, whether a particular form or being possesses an immortal soul, are you not treading perilously near a concept that could easily be construed as heresy? Or is this passage nothing more than the sophmoric pedantry of a young scholar who has manufactured a reason to doubt the immutable fact of his own existence?”

Marcus gulped. Claudo was cutting straight to the point. Are you a heretic or a fool, boy? That was the real question being posed to him now. The Church didn’t burn heretics at the stake anymore, but nevertheless he knew he had to be very careful about what he said next. He closed his eyes and thought quickly before answering.

“Only a philosopher or a fool doubts his own existence, Excellency. It is true, however, that the two all too often prove to be one and the same. I assert that I am neither. The verb ‘to know’ contains a number of interpretations, and in the sentence of which I believe you are speaking, I made use of the concept in its most concrete sense, the sense in which a thing is proven beyond any reasonable possibility of doubt. As in the case, for example, of a mathematical equation.”

Marcus paused. Was that a frown clouding over the Sanctiff’s face? He shook his head, took a deep breath, and tried to clarify his meaning.

“Your Excellency, as you know, where there is surety, there is no faith, no belief per se. And therefore, knowledge of the soul rightly belongs in the realm of faith, not mathematics.”

He placed his right hand over his heart.

“Do I have a soul? Yes, I believe so, with all my heart. But regardless of my faith, it is either so, or it is not, as the Castrate wrote so wisely. My personal belief does not have the capacity to dictate the truth. Indeed, before the eternal Truth of the Almighty God, my own humble opinion is of no account.”

Claudo snorted and his eyes narrowed, but he did not say anything. Father Aestus looked as if he were about to burst out laughing.

The Sanctiff smiled.

“He has you there, Claudo. Unless you did not apprise me of a divine revelation, all your wonderfully conclusive eloquence remain just that—eloquence.”

Claudo shrugged. “It is so. And yet decisions must be made, though the decision-makers be fallible.”

He regarded Marcus coldly and stepped back into the shadows.

Marcus stared at the carpeted floor, chagrined. He wondered what was wrong with his answer, and hoped he hadn’t greatly offended the acerbic ecclesiastic.

“I, too, have a question for the young scholar,” Father Aestus announced. His green eyes danced impishly. “Do you ride?”

“Do I… Horses?” Marcus asked, taken aback.

“I wasn’t thinking of cows,” the Father replied tartly.

“Yes, oh yes. Of course.”

Every Amorran nobleman rode, especially those of the Valerian house. Marcus wondered what kind of trap was being laid for him now. It just didn’t make any sense.

“I have no further questions, your Eminence.”

Father Aestus bowed theatrically to the Sanctiff and joined Bishop Claudo behind the makeshift Sanctal throne.

Marcus was thoroughly confused now, and by this point, wouldn’t have been too surprised if the Sanctiff suddenly leaped out of his chair and demanded that he demonstrate an ability to juggle apples. How was he going to explain this strange business to Sextus?

“I anticipate no objections, then?” the Sanctiff asked the two Churchmen.

“None at all,” Father Aestus said cheerfully. Bishop Claudo slowly shook his head in silence.

“Very well.” A smile creased the Sanctiff’s lined face and he leaned toward Marcus. “I realize this has been a little unusual for you, my son. But I have a problem, you see, and you, Marcus Valerius, are going to help me solve it.”

“Me?” Marcus shook his head. “How could I help you, your Holiness?”

“Let me tell you about my problem first. You see, these illustrious jewels in the crown of the Church,” he nodded toward Claudo and Aestus, “have each penned a marvelous work on Man and his place in this world. The Summa Spiritus you have read. The Ordo Selenus Sapiens you have not, though Father Aestus will no doubt be interested in what you might have to say about it. In many points they are in agreement, but on one very important point they are at variance. It is that particular point which I would like you to help me settle.”

Marcus nodded. “I am yours to command, your Holiness. But what is this point of contention, and how could I ever help you settle it?”

The Sanctiff sighed wearily. “I am an old man, Marcus Valerius, and my days of seeing through this glass darkly will soon come to an end. I cannot travel to Elebrion. I would not survive the trip. But you, my son, shall accompany Bishop Claudo and the good Father in my stead.”

Marcus put his hand over his mouth, and his eyes opened wide with shock. Now he understood what the Sanctiff had in mind, and the sobering realization of terrible responsibility hit him like a blow to the stomach.

“By the blood of the martyrs,” he cried despite himself. “You’re going to decide if the elves have souls!”

Chapter Two

The last vestiges of the setting sun had long since disappeared by the time the small troop of crimson-cloaked guards escorted Marcus past the sturdy gate of his uncle’s domus.

By day, Amorr belonged to God. But its night was claimed by the worst of His creations. Peril lurked in far too many shadows of the narrow, high-walled, circuitous streets called vici. Even a mounted nobleman born to Horse and Sword could find himself beaten, stripped, and if fortunate, merely robbed, by the cruel gangs of half-human breeds and bandits who ravaged the city by night.

Still, even the most lawless of brigands feared crossing the path of the Redeemed, the most fanatical of the Church’s militias. The Redeemed were former gladiators, now rehabilitated—hardened men of violence who had chosen to leave the bloodstained sands of the Coliseum behind them. Slaves they had been and slaves they were still, but they served a different master now.

The glory they now sought was not of this world, and the fervor of their faith was as illustrious as it was utterly ignorant. Not for them, the eloquent debates of Form and Meaning, or Substance and Soul. Marcus was not entirely comfortable in their hulking, creaking, red-cloaked presence, but he appreciated their company in the darkness of the Amorran night.

As they neared the estate, slaves from the household swarmed around Marcus’s horse. He inclined his head politely toward the troop’s commander.

“My thanks, captain. A good evening to you and your men.”

The captain saluted grimly, bringing his fist to his chest, without a hint of personality crossing his scarred, sun-weathered face. He showed no sign of interest in either Marcus or his House. He’d done his duty, nothing more.

“Glory to God, sir.”

Without another word, the ex-gladiator turned his mount around in a swirl of crimson and horsestink. The five Redeemed riders followed him, torches held high, returning confidently into the noisome shadows of the city.

Marcus watched them go, fascinated. He wondered what it would be like to be such a man. To be so sure, so secure in one’s faith, surely that was a wonderful thing! And yet, what was a man’s mind for, if not to use it?

It was another question to ponder, but far less pressing than the one that looked to have him departing on the morning following the morrow. Marcus sighed, and dismounted, waving aside the proffered hands of a tall slave offering him assistance. He patted the soft, fleshy nose of his big grey affectionately before handing the reins over to another slave, this one young, olive-skinned, and thin. But human.

Like most patrician families, it was beneath the dignity of House Valerius to own halfbreeds or inhumans. This slave looked familiar. He wore the blue badge of the stables, but for the life of him Marcus couldn’t remember his name.

“What are you called?” he asked the young slave.

“Deccus, Maester Maercuss,” the boy replied in heavily accented Amorran, not meeting Marcus’s eyes as he carefully stroked the grey’s ears.

Marcus nodded. Now he remembered. The boy was a Bethnian, one of the lot purchased by his uncle’s head steward at the spring auction. Erasto had bought twenty-five or thirty. Bethnians were absurdly inexpensive now thanks to Pontius Balbus’s crushing of a rebellion in that province the year before. But they knew their horses well. Barat would be in good hands with this boy.

“Then please take good care of him tonight, Deccus, and tomorrow as well,” Marcus instructed. “It seems I’ve a journey ahead of me, and he must be fit for the riding.”

The slave nodded, and a faint smile crossed his lips at the sound of his name. The Valerian slaves were treated no worse than most and better than some, but the decuria of the stables was a rough place for a youngster to serve and Marcus knew it could have easily been months since Deccus was last addressed by anything but a curse. The use of the boy’s name might be a small enough kindness, but it counted for something. At least, Marcus hoped that it did.

Rumor spread faster than sickness in the slaves’ quarters, so by the time he entered the atrium Marcipor was already there waiting for him. Marcipor, Marcus’s bodyslave, was a handsome, broad-shouldered man of Savondese descent, the bastard of an officer captured twenty-four years ago by his uncle. They were of the same age, almost to the day.

It was obvious that Sextus had not kept the news of the Sanctiff’s summons to himself, because Marcipor’s blue eyes were alight with curiosity even as they carefully avoided meeting his own. His demeanor was proper—far too proper, in fact—and Marcus stifled a smile as Marcipor overacted with an uncharacteristically elaborate bow as he offered Marcus a fresh tunic of light muslin to replace his dusty day-clothes.

“Why don’t you just come right out and ask me?” Marcus wondered aloud as he held out his arms and let Marcipor assist him out of the sweat-stained tunic.

“This slave would not dream of such presumption, Master.”

Marcus snorted.

“Save it for the girls, pretty boy. My uncle should have sold you to the theater long ago. It’s a pity Pylades didn’t have you for a protégé.”

Marcipor grinned and abandoned the servile pretense. He puffed his chest out and struck a dramatic stance. He was a striking young man, with a strong jaw and a close-cropped, golden beard. More than one slave girl living in the vicinity of the Valerian house had given birth to a fair-haired, blue-eyed baby after Marcipor had passed his sixteenth year.

“Indeed,” he said, “I daresay I would have outshined Hylos. But you must tell me about this mysterious summons. Is it true you saw the Sanctiff? The whole domus has been utterly agog with rumor ever since you left with Father Aurelius! Sextus says they’re going to ordain you early and make you a cardinal!”

“What?” Marcus burst out laughing as he donned a clean tunic. He knew a bishopric was his for the taking. No noble, not even one with plebian blood, would expect anything less. And it was even possible that an archbishopric might be in the cards. But not even a scion of House Severus could hope to be crowned prince of the church before reaching thirty.

“Sextus, as you so often inform me, is an idiot.”

He folded his arms, enjoying the feel of the fresh muslin against his skin A pity he hadn’t the time to visit the baths before vesperna.

“So, what’s the bet?”

He was sure there was a stake involved somehow, for both his cousin and his slave were inveterate gamblers. Marcipor’s coin-hoard far exceeded his own, in fact, more often than not he was in debt to his slave. Marcipor’s rates were usurious, but paying them was easier than trying to extract money from his uncle’s iron fists.

“The archbishopric, of course. Even your lily-white hands aren’t clean enough for the lazulate. Which is a good thing, seeing how you’re barely even a man yet and you’ve too much living to do before you seal yourself up in that white mausoleum for the rest of your life.”

“You’re lying, Marpo.” He knew Marcipor far too well to fall for this. “And if the bet is which one of you I’ll tell first, well, you both lose. I can’t tell you anything. In fact, I don’t even know if I’ll be free to talk to anyone when I return.”

“Return…? So you’re going somewhere!” Marcipor’s face grew calculating for a moment, but then his eyes widened with surprise. “Wait a minute, you can’t go anywhere without me! Unattended? Your uncle would never hear of it! And if you think you’re going to take that irresponsible lunatic of a cousin—”

Marcus held up a hand. “Peace, Marpo.” He yawned and shook his head. “Of course you’re going to go with me. Assuming I go anywhere, that is, for I must ask Magnus’s permission first. But you should probably start getting things together for a six-month journey tonight, because if we do leave, my understanding is that the Sanctiff intends we shall begin the day after tomorrow, and I can’t imagine even Magnus would deny him. Now leave me to attend him. It seems everyone in that ‘white mausoleum’ is too holy to bother with food anymore. I’m hungry enough to eat a boar.”

* * *

The great man was reclining alone in the triclinium, accompanied in his evening meal only by his three favorites.

The room was large, but stark, with no decorations on the white stuccoed walls to detract from the only furniture: a low, tiled table that filled the center of the room and couches on three sides. The colorful tiles told the story of Valerius, the founder of the house, and showed the wounded hero lying in a grove being tended by the wolf who licked his wounds and succored him until his triumphant and vengeful return to Amorr. Magnus often entertained a score or more of Amorr’s great here, senators and equestrians, but fortunately tonight he was as near to alone as Marcus was ever likely to find him.

Lucipor, the ancient, grey-bearded slave who was old enough to be the ex-consul’s father, lay on the couch to his left. Dompor and Lazapor, the household’s resident scholars, shared the couch on the right. As a young girl washed his feet inside the entrance, Marcus could hear Lazapor raising his voice as he took issue with something his uncle had said.

“You underestimate them, Magnus. The villagemen seek no justice, they only slaver after power in the City! What you consider to be an open hand extended in a spirit of generosity, they only see as weakness. Make the mistake of allowing one snake into the Senate, and I assure you, a thousand will soon squirm in behind him!”

Marcus entered barefoot. At the sound of his entrance, his uncle turned to him with what appeared to be relief. There was a rancorous tone to Lazapor’s voice that indicated this evening’s debate was not an entirely civil one. Marcus wondered at his uncle’s habit of engaging in disputation while dining, and yet the custom had clearly not affected the great man’s appetite. Lucius Valerius Magnus, ex-consul and senator, was great in many particulars, not least among them was the impressive size of his paunch.

“I shall, as always, take your words under advisement,” his uncle said to Lazapor. Marcus noted that he had gracefully evaded disclosing his own position on the matter. “Marcus, my dear lad, do come in and rescue me from these disagreeable scholars. Now, is it true that you were summoned to the Sanctorum, or has my son reverted to his childhood custom of telling fanciful tales?”

“Yes,” Dompor said, “we have long expected miracles from you, Marcus, but you seem to have outdone yourself this time. Our darling Sextus is fond of saying that your piety is surpassed only by the Mater Dei. Are we correct in assuming that His Holiness has asked you to serve as his father confessor?”

Marcus usually enjoyed the humor to be found in Dompor’s acerbic tongue, even when he was its target, but this was no time for such indulgences. He smiled faintly at the slave, then met his uncle’s eyes.

“I need to speak with you, Uncle. Alone.”

Magnus’ greying eyebrows rose with surprise, and he raised his hand. Without saying a word, his three companions rose from the couches and departed. Lazapor seemed a little annoyed at the interruption, but Lucipor’s face was marked with concern. Dompor, never one given to worry, appeared amused as he surreptitiously slipped a small bell from his tunic and placed it on the table. For it was not only unusual, it was almost unprecedented, for the great man to banish all three of them from his domestic conclaves.

But Marcus’s strange request did not seem to concern Magnus. He rose with an audible grunt of effort.

“I don’t recall any recent vacancies,” he mused, stroking his chin. “Did Quintus Fulvius die already? I’d heard his see was likely to open soon.”

“It’s not a see, Uncle. I haven’t even decided to take the cloth yet.”

“You haven’t?”

“No, I haven’t, truly,” Marcus insisted, vaguely irritated that everyone else seemed so sure of his future when he himself had not come to a decision yet. The heat of his denial seemed to amuse his uncle, but his amusement vanished as Marcus told him of the Sanctiff’s intentions.

“Elebrion? Sphincterus! That blasted Ahenobarbus bids fair to open up a vat of worms with this notion. I can’t imagine what possesses him to meddle with something that could threaten our northern border while we’re already engaged to the east. Soak my foot, but he always did have a tendency to stick that wretched red beard of his wherever it’s not wanted!”

Marcus blinked. He was unaccustomed to hearing His Holiness, the Sanctified Charity IV, forty-fourth Sanctiff of Amorr, described in such familiar and unflattering terms. Furthermore, the Sanctiff was not only clean-shaven, but his hair had been white as long as Marcus could remember. Red beard? Marcus reached over and took a pair of figs from the bowl on the low table and popped one into his mouth, then took a deep breath and attempted to contradict his uncle.

“I shouldn’t think he’s intending to do anything but learn more—”

“You’re a scholar, Marcus, not a fool. Stop for a moment and think the matter through. Do you think the High King of the elves is so easily hoodwinked? I’ve fought with elves and I’ve fought against them, and I can tell you that if there’s one thing they’re not, it’s fools, my boy. They’re pretty enough, but there’s steel underneath, lad—never forget it! And their blasted wizards have lived ten times longer than our oldest greybeard. Take it from me, Marcus, no one survives that long without learning something, no matter how stupid he might be to start.

“So, they’ll know very well why you’re there, and they’ll know what’s going to happen if those tonsured imbeciles in the Sanctorum completely lose what little remains of their common sense and decide that elves are nothing more than talking beasts.”

The great man shook his head in dismay. “Considering what I’ve heard of King Caerwyn’s court, I imagine he’d consider an infestation of monks preaching celibacy and the church to be an act of war. Tarquin’s tarnation! I suppose we can hope this new High King is cut from a different cloth.”

Marcus waited patiently as his uncle glared at him as if he were a proxy for God’s own viceroy. Despite this unexpected outburst, he still did not believe Magnus would bar him from the journey. There were too many potential advantages to be gained by his participation.

If Marcus took the cloth and was ordained, he would be permanently banned from holding a seat in the Senate. But political power was not the only one in Amorr worth wielding. Marcus’s older brother was the politician of the family, having won election as one of the city’s fifteen Tribunes earlier this year. And his two older sisters had already provided his father with four members of the following generation, including three potential heirs.

The great man’s son, Sexto, had two older brothers who were junior officers in the field serving under his father. A third brother had already successfully stood for tribune. So it was not as if the family were in dire need of another soldier or politician.

When Magnus finally spoke, he laid an avuncular hand the boy’s shoulder. “You’re a good lad, Marcus. Even if Ahenobarbus is sticking his head in a hornet’s nest, the opportunities that will likely present themselves to our house are promising. But be careful! There’s more going on here than you can possibly imagine. Keep your eyes open, keep your wits about you, and don’t let yourself get overly caught up in all that priestly disputation. Try to think about the world you’re in before worrying too much about the one to come.”

“Yes, Magnus.”

“Now, go say goodbye to your mother, but don’t tell her where you are going. Leave that to me. It will be hard on her, with Corvus gone.”

“Yes, Magnus. Although I doubt she’ll even notice I’m not here, not with Tertia’s twins.”

“There is that. I’ll write to your father, lad. He must be apprised of these developments, too. I don’t know if he’ll be terribly pleased, unfortunately, but I’ll knock some sense into him. He expects you to follow in his footsteps. But you were born to think, not brawl or bawl out legionnairies. Oh, and Marcus, you will tell Sextus that he is not to even think of tagging along after you. If he does so much as ride to the Pontus Rossus I’ll have him lashed and halve his allowance for the next three moons.”

Marcus grinned as he bowed respectfully, then reached for the bowl of fruit before departing. Sexto would brave a lashing if need be, but he’d never risk the coin.

“I’ll tell him, Magnus. And thank you, sir. I shall not forget your advice.”

* * *

The great man pursed his lips as he watched his young relation exit the triclinium, an apple in either hand. This news of Elebrion was an unforeseen and unwelcome development. Should he have braved Ahenobarbus’s displeasure and forbidden the old charlatan his nephew? He’d made much harder decisions than this before, given orders that had cost thousands of men their lives without hesitation or regret, and yet something about this one bothered him. Marcus was his brother’s youngest son. In Corvus’s absence, was there not something he could do to safeguard the lad?

The boy was trained, but he was no warrior. His bodyslave was no better: a lover, not a fighter. Perhaps Magnus could send a soldier along to safeguard Marcus. Able soldiers were easy to find, but with them it was discipline that counted most, not skill, and besides, they were taught to fight as a unit.

Perhaps a gladiator?

But gladiators were but men, and Magnus knew all too well the price of a man. What can be bought can always be bought once more by a more generous purse. And it wouldn’t be only elves that would be interested in the buying.

Once word of the prospect of a Church-sanctioned holy war against the elves got out, every petty merchant with a load of tin or cattle skins to sell the legions would be pressing hard to get his fingers into the unending flow of coin that would erupt from the Senate. Worse, he knew very well that some of the more enterprising tradesmen were perfectly capable of taking it upon themselves to help the Sanctiff reach the decision that would be of the most benefit to them.

But what sort of fighting man could not be bought by Man or Elf?

Magnus reached over, took the bell from the table, and shook it. The bronze clang had barely stopped when servant came rushing into the room and nearly collided with him, taken by surprise at his presence out of his recliner

“Find Lucipor,” he commanded. “I want him now. And bring that fool of a son of mine, too. He may be useful for once, as hard as that is to imagine.”

The slave bowed and ran off. He did not, Magnus noted with mild irritation, seem to feel any need to inquire as to which of his sons the senator required.

* * *

Marcus awoke with a start. He sat up on his sweat-damped pallet.

The sun was already risen and a few rays of morning lightened the shadows cast by the thick walls of the domus. Looking around, he discovered that he was alone in the cubiculum, though he did not know if Marcipor had risen before him, or, as seemed more likely, had not returned to the Valerian compound last night.

One of the houseslaves brought him a bowl of water upon request. After he washed his face and hands, he determined to go to the baths as soon as he’d broken his fast. It might well be his last opportunity to do so in quite some time.

He found Sextus already in the triclinium, sprawled in front of a low table laden with fruit, bread and meat left over from the night before. He was idly feeding his dog, a curly-tailed mongrel he’d acquired off the streets the year before.

“You’re up late,” Sextus commented as he popped a piece of orange into his mouth.

“Yes.” Marcus wasn’t that hungry, he realized. He’d eaten rather a lot after speaking with his uncle and his mother.

“How did Aunt Julia take the news of your departure?”

“Placidly.” Marcus ignored the accusatory tone, somewhat surprised that Magnus had seen fit to inform Sextus of his upcoming travels. “Her eyes were dry.”

“Another Aelia, she is,” his cousin said wryly, then laughed.

“You don’t understand the benefit of a father gone campaigning and a mother uninterested in your affairs. I wish Magnus would leave me alone like that. He’s even forbidden me to ride out with you, although I suppose you’ll have that sorry excuse of a slave to keep you company.”

Marcus flicked a grape at his cousin.

“You can’t honestly tell me that you’d abandon Amorr for a long ride through the wilds of Merithaim, Sextus. You do realize that I’m part of an official Church embassy? There won’t be any gambling or girl-chasing, and I don’t recall ecclesiastical debate being one of your favorite pastimes.”

“Chance is everywhere, my dear boy. And wherever there are guards, there you will find men who roll the bones. As for girls, I daresay that Elebrion is full of them!” Sextus’s eyes gleamed wickedly. “Elven girls. I’ve only seen one or two, but they were lovely. Gorgeous! Tall, slender, skin like milk. If you look past the pointy ears and the haughty attitude, why, they might be Vargeyar maidens, and there’s no harm in that!”

“No harm? You wouldn’t survive your first day there. You’d make love to the first sorceress you saw and find yourself turned into a toad before nightfall.”

Sextus paid him no heed.

“Perhaps I shall marry two of them, no, three, actually, and found a new Pannonia. It’s a pity there aren’t more half-elves around these days. Why did we kill them all, do you happen to remember?”

“To spare their women your unseemly lusts,” Marcus said dryly.

He removed a piece of meat from the table, examined it, and tossed it to Sextus’s dog The ugly beast snapped the morsel down with noisy relish.

“I have in mind to go to the baths today, since I don’t think I’ll find one along the Malkanway. Care to join me?”

“Gladly.” Sextus raised a small pouch from under his couch. “We can do that after we take care of this. I have orders to drag you off to the Arena. Believe it or not, that’s what got me out of aiding with the sportulae today. No fights, unfortunately, but since Magnus has correctly ascertained that you and Marpo are able to defend yourselves about as well as a pair of declawed kittens, I’ve orders to take you to the stables and buy you a bodyguard capable of protecting your virtue from those hot-blooded elven slatterns.”

“The Arena? A bodyguard… Do you mean a gladiator?”

“Uh, yes. I know you’ve never been, but you do know what they are, right? Big, bloody-minded brutes, usually knock about trying to kill each other?”

“Why would I need a bodyguard? If the Sanctiff sent six Redeemed to bring me home last night, I’m sure he will ensure that his ambassador is well-guarded in our travels.”

“That’s the problem. I think Magnus wants to make sure that there’s someone who couldn’t care less about the perfumed princes of the Church and will remember to keep an eye on the embassy’s most junior member.”

Marcus shrugged. That made sense, he supposed, although he found it hard to believe that he could possibly be in any real danger. Except, of course, from the elvenking. But if High King Mael decided to attack the embassy, one more bodyguard would hardly make a difference.

* * *

By the time they reached the gladiator stables in the shadow of the Colosseo, Marcus was pleased to step into the dark, low-ceilinged building just to get out of the sun. His pleasure lasted only a moment—the smell of sweat, leather, and blood was so strong that it almost made him reel as he looked around the interior of the wooden structure.

Plaques and weapons adorned the walls, separated by the occasional rude shelf holding bronze and silver cups that Marcus supposed were trophies. Seated at a makeshift desk was a big man laboriously attempting to write numbers on a scroll. It turned out to be the training master working at his accounts.

While the big man raised his eyebrows at Sextus’s request to purchase a gladiator, he was clearly annoyed when Sextus asked to see only dwarves, and only those dwarves fighting under the aegis of the Red faction.

The time it took to summon them seemed like an eternity in that dark and odorous place, but before it became unbearable, the master begrudgingly presented nine of the stocky, broad-shouldered creatures, and Marcus quickly realized the man’s attitude derived from his correct notion that a quick sale was not in order. None of the nine would make for a good travel companion. These dwarves were bitter, angry individuals, degraded into a near-bestial state by the harsh oppression of their slavery.

“Perhaps one of the other factions might have dwarves as well?” Marcus suggested hopefully as the last of the sneering, scowling gladiators was escorted back to the factional cells.

“Not a one,” said the training master. He was a tall, powerfully-built man with a terrible scar across the left side of his face. “Whites don’t take breeds. Greens do, but they usually go in for orcs and gobbos, and those don’t mix real well with dwarves. Blues had twelve until last week, but they all got killed in the re-creation of the Iron Mountain siege.”

“I saw that!” Sextus said. “It was incredible. Especially that catapult they built—for a moment there I thought they were going to turn it on the crowd! Say, why do you shave their beards?”

“Reminds ‘em where they are. Reminds ‘em what they are.” The training master looked appraisingly at Marcus and Sextus, possibly wondering what these two wealthy young masters would want with dwarves in the first place.

“They forget sometimes, else.”

“Are these all you’ve got?” Marcus said. He was doing his best to keep the distaste off his face. Not for the dwarves, for whom he only felt pity, but for the training master. “Isn’t there anyone else?”

The training master shrugged. “There’s two up in the infirmary. I don’t know what you want with a dwarf, but neither one is up to putting up much of a fight. Unless that’s what you want, of course.”

Marcus stared at the man in disbelief. Fortunately, Sextus grabbed his arm and squeezed it before he could open his mouth. What did the man think they were, a pair of decadent thrill killers?

But then, this was Amorr, the greatest city in all the world, and not even its public dedication to the Lord God Almighty enabled it to escape Man’s fallen nature. For every saint here, there were ten sinners, and for every man genuinely devoted to faith, good works, and charity there were three given over to the worst forms of depravity and sadistic decadence. No doubt this man, laboring as he did in this terrible place, saw the evil side of man far more often than its reverse.

“Take ‘em back,” the training master said to an overmuscled pair of assistants. Then he beckoned toward Marcus and Sextus. “Follow me. I’ll take you to the ones in the infirmary. They’re both good fighters, but one was lamed in the last spectacle, and the other one took a pretty good stick in the ribs.”

They followed him up the stairs and into what could easily have passed for one of the lower circles of Hell. The one-room infirmary was dark. It stank of disease and decades of blood dripping from the wounded and dying to soak into the wood of the floor. Marcus was appalled, and he saw even Sextus swallow hard at the olfactory assault on their senses. There were forty beds. A third of them were full, attended by only one slack-jawed attendant, who appeared to be half-witted, at best.

“We keep them alive, if we can,” the training master said, not blind to the reaction of his visitors. “Doesn’t pay to let them die before their time, you know. And it’s not every stable that puts poppyseed in the wine to take the edge off the pain.”

Yes, he was a real humanitarian. Still, it was true: there was none of the moaning and thrashing that Marcus would have expected from such a sad collection of maimed and maltreated individuals. Most were unconscious. The two or three who were not seemed to be lost in a dreamy state that left them blessedly unaware of their surroundings. Marcus did his best to avoid looking directly at any of the ghastly injuries, but even so he saw far more than he would have wished.

The training master stopped at the bedside of a grim-faced dwarf with deep-set eyes, orange-red hair, and a somber mien. He blinked in apparent surprise at being approached.

“This here’s Lodi,” the training master said. “He took a goblin spear in the side six days ago. But he’s a tough old wardog. Took down four or five goblins and two orcs by hisself, just in that one fight alone. He’s left-handed, likes a war hammer—no surprise—but he’s not too shabby with a blade, neither. Not all that quick, but he’s patient and makes for a mean counterfighter. What do you have, Lodi, eighteen wins?”

“Twenty-three,” the dwarf answered in a deep, cracked voice. It sounded as if he had not spoken in days, which was quite possibly the case, considering the level of neglect here. His eyes were glazed with either exhaustion or poppyseed, but he was coherent. “What do you want?”

“A bodyguard,” Marcus answered, stepping forward and meeting the dwarf’s eyes.

Those eyes were dark with suffering, and yet contained none of the hatred or helpless fury that so indelibly marked the rest of his kin. There was a week’s growth of reddish stubble covering his face, but it was clear that not even being clean-shaven had ever caused this dwarf to forget that he had once been free. Blood had seeped through the dirty bandage on his side, but some time ago from the dark, crusted look of it, and there was no sign of green or yellow discharge.

“Can you ride, with that?”

“Won’t make for much of a bodyguard, I’d say,” Sextus commented.

The dwarf’s eyes narrowed.

“A bodyguard?”

“Yes,” Marcus said. “I’m going on a journey and I will require one.”

“Will that get me out of here?” the dwarf asked, glancing at the training master, who nodded. “You’ll have to tie me to the beast, I think, but you’ll hear no complaints from me, even if it chafes me raw.”

“Or you bleed to death?”

The dwarf turned toward Sextus, and the wordless reproach in his dark eyes caused Sextus to fall silent.

“Come in,” he called, resigned.

The latch creaked, and a familiar, sun-bronzed face peered around the corner of the door. It belonged to his cousin Sextus, whose brown eyes were dancing with mischief.

“This better be good,” Marcus warned him. “I was just getting to the part where the tribal chief is about to sacrifice the centurion to his devil-gods.”

Sextus nodded absently. “Oh, yes, you said you were going to read up on old Quintus, didn’t you? Well, if it’ll save you some time, I’ll tell you how it ends. The legions march in, the heathen see the error of their ways, and Amorr triumphs over all. Hallelujah and amen!”

Marcus stared at him, and with some difficulty, rejected the first three responses that leaped to mind. “Thank you, Sexto. Your help is…beyond words. Now, go away, please.”

His cousin grinned back at him, and maddeningly, did not leave but rather folded his arms and leaned against the edge of the entryway.

Sexto was a half-hand shorter than Marcus, but with a slim build that made him appear taller. Like Marcus and the rest of their family, his eyes were dark brown, but he was no scholar and his skin was deeply bronzed by the sun. He wore a plain white tunica devoid of any equestrian stripes, he was barefoot, and his belt was an unadorned strip of worn leather. Besides the intrinsic arrogance that radiated from him like heat from a fire, only the finely carved silver buckle clasping the belt showed any sign that he was a Senator’s son, let alone a Valerian.

“Don’t you want to know why I’m here?”

“To plague me?” Marcus guessed. “To keep me from my learning?”

Sextus steepled his hands and did his best to appear pious. The effect would have worked better if he had stopped smirking first.

“I’m here in my priestly capacity, believe it or not. The Father Superior sent me with a message for you. You’re to go before the Sanctiff.”

“What?” Marcus was sure he hadn’t heard correctly. “I’m supposed to go where?”

“To the Sanctiff,” Sextus repeated. “Yes, you, and right away, too. Father Aurelius is already on his way here—he’s to escort you to the Palace.”

He grinned and arched his eyebrows. “Now tell me what you did to get in that kind of trouble, Marco! Did I miss out on something?”

Marcus swallowed hard. This wasn’t just impossible, it was beyond imagining. Amorr had no king. The Lord God Himself ruled over the Republic. However, as the earthly head of the Amorran Church, the Sanctiff was His voice and His viceroy from the banks of the Tiburon to the shores of the Rialthan Sea.

And Marcus had no idea why the Sanctiff wanted to see him. No idea at all.

* * *

The Holy Palace boasted twelve spires ringing one massive cupola, a symbolic representation in marble of mankind’s Savior and His twelve disciples. Marcus, with Father Aurelius by his side, were being escorted into it by the Palace’s hard-faced soldiers with their red cloaks.

To Marcus’s relief they did not march him into the Hall of Judgment. That place was dreaded by every sane and sober Amorran. He had first feared they were taking him there to stand before some inquest. But instead the guards conducted them to what appeared to be a small, private antechamber just off one of the palace’s central corridors.

The room was dark, lit only by seven guttering rushlights. It was cool, but not cold, and two of the stucco walls were obscured with wooden shelves that held fat scrolls of various lengths. Marcus couldn’t see the back wall behind the lights, but he stopped looking about the room when his eyes alighted upon an elderly man sitting alone in its center.

His Holiness was reclining on an unimposing, leather-wrapped chair that looked as comfortable as it was worn with age. He wore none of the trappings of his awesome office, only the simple blue robe of a Jamite brother. The robe was darker than his cerulean eyes, which were encased by thin folds of sagging flesh and surmounted by a pair of bushy white eyebrows. But he smiled warmly at his visitors, and Marcus could easily have thought of him as someone’s good-humored paterfamilias were it not for the gem-encrusted ring of office adorning his left hand.

“Thank you for coming, Father Aurelius.” The Sanctiff’s voice was deep, but to hear it up close in this small room instead of echoing off the marble of the palace steps made it seem more friendly than intimidating. “I have received excellent reports of your work with the junior scholastics. And welcome, Marcus Valerius. I wished to see with my own eyes the latest prodigy of the Valerian House. Perhaps you shall do for the Church what your illustrious forebears have done for Amorr’s legions, hmmm?”

Marcus blushed before the Sanctiff’s praise. It was as if the old man had seen into his mind and read his deepest, most hidden desires.

“Thank you, your Holiness. I only seek to serve God and Amorr, to the best of my small abilities.”

The Sanctiff’s aged lips wrinkled in a wry smile, and he glanced toward the shadowy corner of the room.

“Admirably courteous, is he not? I should think any concerns regarding his comportment are groundless. Don’t you agree, Caecilus Cassius?”

Marcus drew in a sharp breath as a thin-faced man in a black robe emerged from the darkness, accompanied by a cheerful-looking Jamite priest in the blue robe of his order.

Marcus knew the man whom His Holiness addressed so familiarly. Or rather, he knew of him. Caecilus Cassius Claudo was the Bishop of Avienne, one of the Church’s leading intellectuals. His famous treatise, the Summa Spiritus, written on all the diverse races of Selenoth and their distinct places in the Will of God, had sparked a raging flame of lively debate that still roared through every scholastic circle in the Republic. Marcus himself had written a short commentary on the Summa less than a year ago.

“That remains to be seen, your Holiness.” Claudo’s arid voice was acerbic and high-pitched. “Certainly, a number of his expressed opinions are impudent in the extreme.”

“Oh, come now, Claudo,” the Jamite broke in, laughing. His round face was ruddy, and Marcus liked him immediately. “A refusal to abase himself before your lofty eminence does not indicate an inclination towards boorish behavior. Why, it’s nothing more than a sign of sheer good sense!”

He smiled broadly, making it clear that he was only teasing his proud colleague, then graciously inclined his head towards Marcus and Father Aurelius.

“Since His Holiness does not see fit to introduce us, I shall take the matter in hand myself. I am Quintus Servilius Aestus, a humble priest in service to the Lord Immanuel, and, of course, His Holiness. My distinguished colleague is none other than His Excellency, the Bishop of Avienus, whose work I believe you know quite well.”

Father Aestus shook their hands warmly, first Father Aurelius’s, then Marcus’s own. Marcus was in awe, for he was truly in the presence of greatness—not once, not twice, but three times over. Father Aestus was one of the few intellectuals who dared to publicly cross wits with the famed Bishop, and he was rumored to be working on his own magnum opus in opposition to Cassius Claudo’s brilliant masterpiece.

The Sanctiff cleared his throat, and Father Aestus smoothly effaced himself, but not before directing a disconcerting wink at Marcus.

“Father Aurelius, you know why I have summoned you,” the Sanctiff stated, “and your presence here answers the question I posed to you earlier. However, Bishop Claudo and Father Aestus have their own questions for your young scholar, and with your permission, I would allow them to inquire of him.”

“Of course, your Holiness,” Father Aurelius replied obediently. He was an astute man, and did not need to be told when his presence was not required. “May I have your permission to withdraw, your Holiness?”

“Go with God, Father,” the Sanctiff said, extending his left hand. “And the grace of Our Living Lord be upon you.”

Father Aurelius bent over and kissed the sacerdotal ring of office, then gave Marcus a reassuring pat on the shoulder as he left the room. Marcus suddenly felt alone and intimidated, surrounded as he was by three of the republic’s most formidable minds.

Bishop Claudo’s dry voice broke in on his thoughts. “Marcus Valerius, I have read your commentary on the Summa Spiritus. It is…not without merit. But when you say that one does not know, indeed, that one is not even capable of knowing, whether a particular form or being possesses an immortal soul, are you not treading perilously near a concept that could easily be construed as heresy? Or is this passage nothing more than the sophmoric pedantry of a young scholar who has manufactured a reason to doubt the immutable fact of his own existence?”

Marcus gulped. Claudo was cutting straight to the point. Are you a heretic or a fool, boy? That was the real question being posed to him now. The Church didn’t burn heretics at the stake anymore, but nevertheless he knew he had to be very careful about what he said next. He closed his eyes and thought quickly before answering.

“Only a philosopher or a fool doubts his own existence, Excellency. It is true, however, that the two all too often prove to be one and the same. I assert that I am neither. The verb ‘to know’ contains a number of interpretations, and in the sentence of which I believe you are speaking, I made use of the concept in its most concrete sense, the sense in which a thing is proven beyond any reasonable possibility of doubt. As in the case, for example, of a mathematical equation.”

Marcus paused. Was that a frown clouding over the Sanctiff’s face? He shook his head, took a deep breath, and tried to clarify his meaning.

“Your Excellency, as you know, where there is surety, there is no faith, no belief per se. And therefore, knowledge of the soul rightly belongs in the realm of faith, not mathematics.”

He placed his right hand over his heart.

“Do I have a soul? Yes, I believe so, with all my heart. But regardless of my faith, it is either so, or it is not, as the Castrate wrote so wisely. My personal belief does not have the capacity to dictate the truth. Indeed, before the eternal Truth of the Almighty God, my own humble opinion is of no account.”

Claudo snorted and his eyes narrowed, but he did not say anything. Father Aestus looked as if he were about to burst out laughing.

The Sanctiff smiled.

“He has you there, Claudo. Unless you did not apprise me of a divine revelation, all your wonderfully conclusive eloquence remain just that—eloquence.”

Claudo shrugged. “It is so. And yet decisions must be made, though the decision-makers be fallible.”

He regarded Marcus coldly and stepped back into the shadows.

Marcus stared at the carpeted floor, chagrined. He wondered what was wrong with his answer, and hoped he hadn’t greatly offended the acerbic ecclesiastic.

“I, too, have a question for the young scholar,” Father Aestus announced. His green eyes danced impishly. “Do you ride?”

“Do I… Horses?” Marcus asked, taken aback.

“I wasn’t thinking of cows,” the Father replied tartly.

“Yes, oh yes. Of course.”

Every Amorran nobleman rode, especially those of the Valerian house. Marcus wondered what kind of trap was being laid for him now. It just didn’t make any sense.

“I have no further questions, your Eminence.”

Father Aestus bowed theatrically to the Sanctiff and joined Bishop Claudo behind the makeshift Sanctal throne.

Marcus was thoroughly confused now, and by this point, wouldn’t have been too surprised if the Sanctiff suddenly leaped out of his chair and demanded that he demonstrate an ability to juggle apples. How was he going to explain this strange business to Sextus?

“I anticipate no objections, then?” the Sanctiff asked the two Churchmen.

“None at all,” Father Aestus said cheerfully. Bishop Claudo slowly shook his head in silence.

“Very well.” A smile creased the Sanctiff’s lined face and he leaned toward Marcus. “I realize this has been a little unusual for you, my son. But I have a problem, you see, and you, Marcus Valerius, are going to help me solve it.”

“Me?” Marcus shook his head. “How could I help you, your Holiness?”

“Let me tell you about my problem first. You see, these illustrious jewels in the crown of the Church,” he nodded toward Claudo and Aestus, “have each penned a marvelous work on Man and his place in this world. The Summa Spiritus you have read. The Ordo Selenus Sapiens you have not, though Father Aestus will no doubt be interested in what you might have to say about it. In many points they are in agreement, but on one very important point they are at variance. It is that particular point which I would like you to help me settle.”

Marcus nodded. “I am yours to command, your Holiness. But what is this point of contention, and how could I ever help you settle it?”

The Sanctiff sighed wearily. “I am an old man, Marcus Valerius, and my days of seeing through this glass darkly will soon come to an end. I cannot travel to Elebrion. I would not survive the trip. But you, my son, shall accompany Bishop Claudo and the good Father in my stead.”

Marcus put his hand over his mouth, and his eyes opened wide with shock. Now he understood what the Sanctiff had in mind, and the sobering realization of terrible responsibility hit him like a blow to the stomach.

“By the blood of the martyrs,” he cried despite himself. “You’re going to decide if the elves have souls!”

Chapter Two

The last vestiges of the setting sun had long since disappeared by the time the small troop of crimson-cloaked guards escorted Marcus past the sturdy gate of his uncle’s domus.

By day, Amorr belonged to God. But its night was claimed by the worst of His creations. Peril lurked in far too many shadows of the narrow, high-walled, circuitous streets called vici. Even a mounted nobleman born to Horse and Sword could find himself beaten, stripped, and if fortunate, merely robbed, by the cruel gangs of half-human breeds and bandits who ravaged the city by night.

Still, even the most lawless of brigands feared crossing the path of the Redeemed, the most fanatical of the Church’s militias. The Redeemed were former gladiators, now rehabilitated—hardened men of violence who had chosen to leave the bloodstained sands of the Coliseum behind them. Slaves they had been and slaves they were still, but they served a different master now.

The glory they now sought was not of this world, and the fervor of their faith was as illustrious as it was utterly ignorant. Not for them, the eloquent debates of Form and Meaning, or Substance and Soul. Marcus was not entirely comfortable in their hulking, creaking, red-cloaked presence, but he appreciated their company in the darkness of the Amorran night.

As they neared the estate, slaves from the household swarmed around Marcus’s horse. He inclined his head politely toward the troop’s commander.

“My thanks, captain. A good evening to you and your men.”

The captain saluted grimly, bringing his fist to his chest, without a hint of personality crossing his scarred, sun-weathered face. He showed no sign of interest in either Marcus or his House. He’d done his duty, nothing more.

“Glory to God, sir.”

Without another word, the ex-gladiator turned his mount around in a swirl of crimson and horsestink. The five Redeemed riders followed him, torches held high, returning confidently into the noisome shadows of the city.

Marcus watched them go, fascinated. He wondered what it would be like to be such a man. To be so sure, so secure in one’s faith, surely that was a wonderful thing! And yet, what was a man’s mind for, if not to use it?

It was another question to ponder, but far less pressing than the one that looked to have him departing on the morning following the morrow. Marcus sighed, and dismounted, waving aside the proffered hands of a tall slave offering him assistance. He patted the soft, fleshy nose of his big grey affectionately before handing the reins over to another slave, this one young, olive-skinned, and thin. But human.

Like most patrician families, it was beneath the dignity of House Valerius to own halfbreeds or inhumans. This slave looked familiar. He wore the blue badge of the stables, but for the life of him Marcus couldn’t remember his name.

“What are you called?” he asked the young slave.

“Deccus, Maester Maercuss,” the boy replied in heavily accented Amorran, not meeting Marcus’s eyes as he carefully stroked the grey’s ears.

Marcus nodded. Now he remembered. The boy was a Bethnian, one of the lot purchased by his uncle’s head steward at the spring auction. Erasto had bought twenty-five or thirty. Bethnians were absurdly inexpensive now thanks to Pontius Balbus’s crushing of a rebellion in that province the year before. But they knew their horses well. Barat would be in good hands with this boy.

“Then please take good care of him tonight, Deccus, and tomorrow as well,” Marcus instructed. “It seems I’ve a journey ahead of me, and he must be fit for the riding.”

The slave nodded, and a faint smile crossed his lips at the sound of his name. The Valerian slaves were treated no worse than most and better than some, but the decuria of the stables was a rough place for a youngster to serve and Marcus knew it could have easily been months since Deccus was last addressed by anything but a curse. The use of the boy’s name might be a small enough kindness, but it counted for something. At least, Marcus hoped that it did.

Rumor spread faster than sickness in the slaves’ quarters, so by the time he entered the atrium Marcipor was already there waiting for him. Marcipor, Marcus’s bodyslave, was a handsome, broad-shouldered man of Savondese descent, the bastard of an officer captured twenty-four years ago by his uncle. They were of the same age, almost to the day.

It was obvious that Sextus had not kept the news of the Sanctiff’s summons to himself, because Marcipor’s blue eyes were alight with curiosity even as they carefully avoided meeting his own. His demeanor was proper—far too proper, in fact—and Marcus stifled a smile as Marcipor overacted with an uncharacteristically elaborate bow as he offered Marcus a fresh tunic of light muslin to replace his dusty day-clothes.

“Why don’t you just come right out and ask me?” Marcus wondered aloud as he held out his arms and let Marcipor assist him out of the sweat-stained tunic.

“This slave would not dream of such presumption, Master.”

Marcus snorted.

“Save it for the girls, pretty boy. My uncle should have sold you to the theater long ago. It’s a pity Pylades didn’t have you for a protégé.”

Marcipor grinned and abandoned the servile pretense. He puffed his chest out and struck a dramatic stance. He was a striking young man, with a strong jaw and a close-cropped, golden beard. More than one slave girl living in the vicinity of the Valerian house had given birth to a fair-haired, blue-eyed baby after Marcipor had passed his sixteenth year.

“Indeed,” he said, “I daresay I would have outshined Hylos. But you must tell me about this mysterious summons. Is it true you saw the Sanctiff? The whole domus has been utterly agog with rumor ever since you left with Father Aurelius! Sextus says they’re going to ordain you early and make you a cardinal!”

“What?” Marcus burst out laughing as he donned a clean tunic. He knew a bishopric was his for the taking. No noble, not even one with plebian blood, would expect anything less. And it was even possible that an archbishopric might be in the cards. But not even a scion of House Severus could hope to be crowned prince of the church before reaching thirty.

“Sextus, as you so often inform me, is an idiot.”

He folded his arms, enjoying the feel of the fresh muslin against his skin A pity he hadn’t the time to visit the baths before vesperna.

“So, what’s the bet?”

He was sure there was a stake involved somehow, for both his cousin and his slave were inveterate gamblers. Marcipor’s coin-hoard far exceeded his own, in fact, more often than not he was in debt to his slave. Marcipor’s rates were usurious, but paying them was easier than trying to extract money from his uncle’s iron fists.

“The archbishopric, of course. Even your lily-white hands aren’t clean enough for the lazulate. Which is a good thing, seeing how you’re barely even a man yet and you’ve too much living to do before you seal yourself up in that white mausoleum for the rest of your life.”

“You’re lying, Marpo.” He knew Marcipor far too well to fall for this. “And if the bet is which one of you I’ll tell first, well, you both lose. I can’t tell you anything. In fact, I don’t even know if I’ll be free to talk to anyone when I return.”

“Return…? So you’re going somewhere!” Marcipor’s face grew calculating for a moment, but then his eyes widened with surprise. “Wait a minute, you can’t go anywhere without me! Unattended? Your uncle would never hear of it! And if you think you’re going to take that irresponsible lunatic of a cousin—”

Marcus held up a hand. “Peace, Marpo.” He yawned and shook his head. “Of course you’re going to go with me. Assuming I go anywhere, that is, for I must ask Magnus’s permission first. But you should probably start getting things together for a six-month journey tonight, because if we do leave, my understanding is that the Sanctiff intends we shall begin the day after tomorrow, and I can’t imagine even Magnus would deny him. Now leave me to attend him. It seems everyone in that ‘white mausoleum’ is too holy to bother with food anymore. I’m hungry enough to eat a boar.”

* * *

The great man was reclining alone in the triclinium, accompanied in his evening meal only by his three favorites.

The room was large, but stark, with no decorations on the white stuccoed walls to detract from the only furniture: a low, tiled table that filled the center of the room and couches on three sides. The colorful tiles told the story of Valerius, the founder of the house, and showed the wounded hero lying in a grove being tended by the wolf who licked his wounds and succored him until his triumphant and vengeful return to Amorr. Magnus often entertained a score or more of Amorr’s great here, senators and equestrians, but fortunately tonight he was as near to alone as Marcus was ever likely to find him.

Lucipor, the ancient, grey-bearded slave who was old enough to be the ex-consul’s father, lay on the couch to his left. Dompor and Lazapor, the household’s resident scholars, shared the couch on the right. As a young girl washed his feet inside the entrance, Marcus could hear Lazapor raising his voice as he took issue with something his uncle had said.

“You underestimate them, Magnus. The villagemen seek no justice, they only slaver after power in the City! What you consider to be an open hand extended in a spirit of generosity, they only see as weakness. Make the mistake of allowing one snake into the Senate, and I assure you, a thousand will soon squirm in behind him!”

Marcus entered barefoot. At the sound of his entrance, his uncle turned to him with what appeared to be relief. There was a rancorous tone to Lazapor’s voice that indicated this evening’s debate was not an entirely civil one. Marcus wondered at his uncle’s habit of engaging in disputation while dining, and yet the custom had clearly not affected the great man’s appetite. Lucius Valerius Magnus, ex-consul and senator, was great in many particulars, not least among them was the impressive size of his paunch.

“I shall, as always, take your words under advisement,” his uncle said to Lazapor. Marcus noted that he had gracefully evaded disclosing his own position on the matter. “Marcus, my dear lad, do come in and rescue me from these disagreeable scholars. Now, is it true that you were summoned to the Sanctorum, or has my son reverted to his childhood custom of telling fanciful tales?”

“Yes,” Dompor said, “we have long expected miracles from you, Marcus, but you seem to have outdone yourself this time. Our darling Sextus is fond of saying that your piety is surpassed only by the Mater Dei. Are we correct in assuming that His Holiness has asked you to serve as his father confessor?”

Marcus usually enjoyed the humor to be found in Dompor’s acerbic tongue, even when he was its target, but this was no time for such indulgences. He smiled faintly at the slave, then met his uncle’s eyes.

“I need to speak with you, Uncle. Alone.”

Magnus’ greying eyebrows rose with surprise, and he raised his hand. Without saying a word, his three companions rose from the couches and departed. Lazapor seemed a little annoyed at the interruption, but Lucipor’s face was marked with concern. Dompor, never one given to worry, appeared amused as he surreptitiously slipped a small bell from his tunic and placed it on the table. For it was not only unusual, it was almost unprecedented, for the great man to banish all three of them from his domestic conclaves.

But Marcus’s strange request did not seem to concern Magnus. He rose with an audible grunt of effort.

“I don’t recall any recent vacancies,” he mused, stroking his chin. “Did Quintus Fulvius die already? I’d heard his see was likely to open soon.”

“It’s not a see, Uncle. I haven’t even decided to take the cloth yet.”

“You haven’t?”

“No, I haven’t, truly,” Marcus insisted, vaguely irritated that everyone else seemed so sure of his future when he himself had not come to a decision yet. The heat of his denial seemed to amuse his uncle, but his amusement vanished as Marcus told him of the Sanctiff’s intentions.

“Elebrion? Sphincterus! That blasted Ahenobarbus bids fair to open up a vat of worms with this notion. I can’t imagine what possesses him to meddle with something that could threaten our northern border while we’re already engaged to the east. Soak my foot, but he always did have a tendency to stick that wretched red beard of his wherever it’s not wanted!”

Marcus blinked. He was unaccustomed to hearing His Holiness, the Sanctified Charity IV, forty-fourth Sanctiff of Amorr, described in such familiar and unflattering terms. Furthermore, the Sanctiff was not only clean-shaven, but his hair had been white as long as Marcus could remember. Red beard? Marcus reached over and took a pair of figs from the bowl on the low table and popped one into his mouth, then took a deep breath and attempted to contradict his uncle.

“I shouldn’t think he’s intending to do anything but learn more—”

“You’re a scholar, Marcus, not a fool. Stop for a moment and think the matter through. Do you think the High King of the elves is so easily hoodwinked? I’ve fought with elves and I’ve fought against them, and I can tell you that if there’s one thing they’re not, it’s fools, my boy. They’re pretty enough, but there’s steel underneath, lad—never forget it! And their blasted wizards have lived ten times longer than our oldest greybeard. Take it from me, Marcus, no one survives that long without learning something, no matter how stupid he might be to start.

“So, they’ll know very well why you’re there, and they’ll know what’s going to happen if those tonsured imbeciles in the Sanctorum completely lose what little remains of their common sense and decide that elves are nothing more than talking beasts.”

The great man shook his head in dismay. “Considering what I’ve heard of King Caerwyn’s court, I imagine he’d consider an infestation of monks preaching celibacy and the church to be an act of war. Tarquin’s tarnation! I suppose we can hope this new High King is cut from a different cloth.”

Marcus waited patiently as his uncle glared at him as if he were a proxy for God’s own viceroy. Despite this unexpected outburst, he still did not believe Magnus would bar him from the journey. There were too many potential advantages to be gained by his participation.

If Marcus took the cloth and was ordained, he would be permanently banned from holding a seat in the Senate. But political power was not the only one in Amorr worth wielding. Marcus’s older brother was the politician of the family, having won election as one of the city’s fifteen Tribunes earlier this year. And his two older sisters had already provided his father with four members of the following generation, including three potential heirs.

The great man’s son, Sexto, had two older brothers who were junior officers in the field serving under his father. A third brother had already successfully stood for tribune. So it was not as if the family were in dire need of another soldier or politician.

When Magnus finally spoke, he laid an avuncular hand the boy’s shoulder. “You’re a good lad, Marcus. Even if Ahenobarbus is sticking his head in a hornet’s nest, the opportunities that will likely present themselves to our house are promising. But be careful! There’s more going on here than you can possibly imagine. Keep your eyes open, keep your wits about you, and don’t let yourself get overly caught up in all that priestly disputation. Try to think about the world you’re in before worrying too much about the one to come.”

“Yes, Magnus.”

“Now, go say goodbye to your mother, but don’t tell her where you are going. Leave that to me. It will be hard on her, with Corvus gone.”

“Yes, Magnus. Although I doubt she’ll even notice I’m not here, not with Tertia’s twins.”

“There is that. I’ll write to your father, lad. He must be apprised of these developments, too. I don’t know if he’ll be terribly pleased, unfortunately, but I’ll knock some sense into him. He expects you to follow in his footsteps. But you were born to think, not brawl or bawl out legionnairies. Oh, and Marcus, you will tell Sextus that he is not to even think of tagging along after you. If he does so much as ride to the Pontus Rossus I’ll have him lashed and halve his allowance for the next three moons.”

Marcus grinned as he bowed respectfully, then reached for the bowl of fruit before departing. Sexto would brave a lashing if need be, but he’d never risk the coin.

“I’ll tell him, Magnus. And thank you, sir. I shall not forget your advice.”

* * *

The great man pursed his lips as he watched his young relation exit the triclinium, an apple in either hand. This news of Elebrion was an unforeseen and unwelcome development. Should he have braved Ahenobarbus’s displeasure and forbidden the old charlatan his nephew? He’d made much harder decisions than this before, given orders that had cost thousands of men their lives without hesitation or regret, and yet something about this one bothered him. Marcus was his brother’s youngest son. In Corvus’s absence, was there not something he could do to safeguard the lad?

The boy was trained, but he was no warrior. His bodyslave was no better: a lover, not a fighter. Perhaps Magnus could send a soldier along to safeguard Marcus. Able soldiers were easy to find, but with them it was discipline that counted most, not skill, and besides, they were taught to fight as a unit.

Perhaps a gladiator?

But gladiators were but men, and Magnus knew all too well the price of a man. What can be bought can always be bought once more by a more generous purse. And it wouldn’t be only elves that would be interested in the buying.

Once word of the prospect of a Church-sanctioned holy war against the elves got out, every petty merchant with a load of tin or cattle skins to sell the legions would be pressing hard to get his fingers into the unending flow of coin that would erupt from the Senate. Worse, he knew very well that some of the more enterprising tradesmen were perfectly capable of taking it upon themselves to help the Sanctiff reach the decision that would be of the most benefit to them.

But what sort of fighting man could not be bought by Man or Elf?

Magnus reached over, took the bell from the table, and shook it. The bronze clang had barely stopped when servant came rushing into the room and nearly collided with him, taken by surprise at his presence out of his recliner

“Find Lucipor,” he commanded. “I want him now. And bring that fool of a son of mine, too. He may be useful for once, as hard as that is to imagine.”

The slave bowed and ran off. He did not, Magnus noted with mild irritation, seem to feel any need to inquire as to which of his sons the senator required.

* * *